“Education has to be at the forefront of restoring this country,” said Bard College President Leon Botstein today, at a ceremony formally welcoming incoming Simon’s Rock provost Peter Laipson to his new post.

“Education has to be at the forefront of restoring this country,” said Bard College President Leon Botstein today, at a ceremony formally welcoming incoming Simon’s Rock provost Peter Laipson to his new post.

“The problem with America is an absence of discipline and an unwillingness to confront unpleasant truths,” Leon continued, elegantly making the case for liberal arts education as a crucial piece of the on-going struggle to bring our country back to its core values of democracy, tolerance and creativity.

Most importantly, he said, “young people need the tools to be able to think for themselves.”

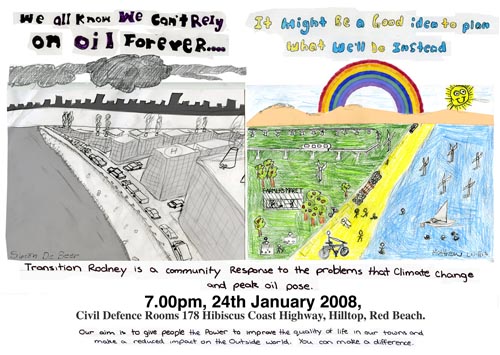

So true–and yet this kind of active learning has to start long before the college level! I contrast Leon’s remarks today with the parents’ open house I attended last week at my son’s middle school, where all of the teachers made reference to how their lesson plans included preparation for the MCAS exams (the Massachusetts version of the No Child Left Behind federally mandated standardized tests), which the 7th graders will be taking next spring.

So true–and yet this kind of active learning has to start long before the college level! I contrast Leon’s remarks today with the parents’ open house I attended last week at my son’s middle school, where all of the teachers made reference to how their lesson plans included preparation for the MCAS exams (the Massachusetts version of the No Child Left Behind federally mandated standardized tests), which the 7th graders will be taking next spring.

The middle school principal, in his welcoming remarks, talked about school as a place to ignite students’ passions, but once the teachers took the stage there wasn’t much talk of passion, nor of the kind of student-centered learning that helps kids find out what they’re interested in.

In today’s networked world, kids don’t need to memorize information or formulas. They need to be turned on to the excitement of learning; they need to be encouraged to develop their creativity, to take the risk of venturing into unexplored conceptual territory, to become the innovators our society so desperately needs.

It was good to hear Leon Botstein and Peter Laipson affirm Elizabeth Blodgett Hall, the founder of Simon’s Rock, as a social entrepreneur who wasn’t afraid to take risks, and who dreamed big and had the staying power to manifest her vision of an early college–a completely new idea back in 1966, and still quite unorthodox today.

It was good to hear Leon Botstein and Peter Laipson affirm Elizabeth Blodgett Hall, the founder of Simon’s Rock, as a social entrepreneur who wasn’t afraid to take risks, and who dreamed big and had the staying power to manifest her vision of an early college–a completely new idea back in 1966, and still quite unorthodox today.

Betty Hall realized that some high school students have the intellectual and social maturity to start college after the 10th grade, and she took the risk of actually trying it out. The rest is history–the history of Simon’s Rock, now known as Bard College at Simon’s Rock.

As a Simon’s Rock alum (I earned my B.A. in English and journalism there in 1982) I can attest to the excitement of switching from the dull routine of high school to the much more intense small-group discussions that characterized Simon’s Rock classes then, and still do today.

As a Simon’s Rock alum (I earned my B.A. in English and journalism there in 1982) I can attest to the excitement of switching from the dull routine of high school to the much more intense small-group discussions that characterized Simon’s Rock classes then, and still do today.

I went to an excellent high school, Hunter College High School–and yet once I got to Simon’s Rock, in part because of the interesting, stimulating peer group, I was clearly in a whole new ballgame. I was indeed encouraged to explore my passions, which at the time were reading and writing. Under the guidance of outstanding mentors, I wrote a B.A. thesis on androgyny in the novels of Virginia Woolf, while working part-time as a reporter for The Berkshire Courier, the Great Barrington weekly newspaper. I credit those two experiences with the whole unfolding of my subsequent career, from the Ph.D. in literature to the on-going interest in and practice of journalism and media studies.

Leon is right that education has a key role to play in turning our country around. Unfortunately, as I wrote in an earlier post, even at the college level things are not what they used to be, as the tenured faculty gives way to legions of adjuncts–freelancers with Ph.Ds–who now are frequently not even on campus, but rather teaching through distance learning platforms from their homes.

It’s too soon to weigh the pros and cons of distance learning. It has the potential to be emancipatory, accessible to far more students, including those who could not afford the luxury of a four-year residential liberal arts education of the kind Leon Botstein was talking about today. It could also turn into the worst kind of cookie-cutter education, MCAS on steroids.

One of the tasks of educators today has to be to enter with spirit into the unfolding of the distance learning revolution, making sure the technology is being used to promote active learning and critical thinking, not rote learning or multiple choice testing. We also have to make sure that networked computer technology actually connects young people, rather than alienating them from each other and from potential mentors.

As Leon said, it’s not a question of teaching students to believe any particular truths or ways of seeing the world, it’s a question of enabling them to make their own informed observations, and giving them the tools to act on what they see and know. We’re not talking about education as indoctrination, but about education as the constant opening of new doors to further understanding–a never-ending process that should not, and cannot be confined merely to the classroom.

As Leon said, it’s not a question of teaching students to believe any particular truths or ways of seeing the world, it’s a question of enabling them to make their own informed observations, and giving them the tools to act on what they see and know. We’re not talking about education as indoctrination, but about education as the constant opening of new doors to further understanding–a never-ending process that should not, and cannot be confined merely to the classroom.

Communicating the excitement of learning is the single most important role of a teacher at any grade level. Once we teachers become jaded or bored with what we’re offering, it’s all over. We have to find ways of making it new, by constantly leaving ourselves open to new ideas and viewpoints. Often for me, it’s the students themselves who lead the way into new ways of seeing familiar texts or concepts.

It can be hard for a teacher to give up the powerful illusion of being the one who knows all the answers. The truth is, we’re here to enable the next generation of thinkers to imagine questions that have not yet been asked or even thought of.

What could be more exciting than that?

Josh Haner/The New York Times)

Josh Haner/The New York Times)