We raise our children so carefully, so thoughtfully. We make them eat their vegetables, organic if possible. We send them to the best schools we can find and afford. We screen their friends and text them anxiously if they’re late coming home. We worry about their careers, their futures. Will there be any jobs for our precious children when we finally, with great effort and care, get them through high school and college?

Jobs are important, sure. But why is it easier for us to think about the economy than about the biggest issue confronting our children, and all of us, in the next few years? I’m talking about the climate crisis and the degradation of the environment. The loss of species, the toxifying of the air, soil and water. The fact that the planet our children are inheriting is not the planet we were born on to.

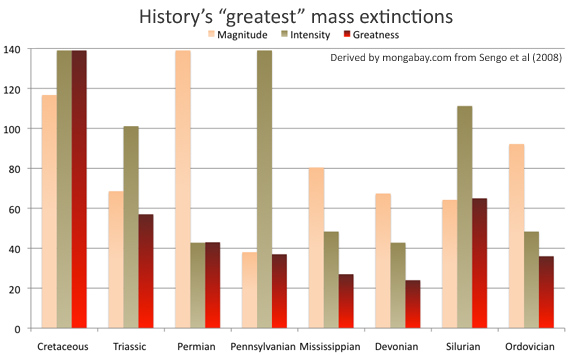

Of course, that’s always been true. The planet has always been changing, evolving, sometimes in violent increments. But it’s different now. It’s different because never before, in the history of homo sapiens, have we been so close to the brink of a major, fast shift in our climate. Never before, at least since we humans have been on the planetary stage, have we come so close to a global extinction event.

Global extinction event. Where did I get a phrase like that? It’s surely not my own language. It’s one of those memes making the rounds of the Web. But it’s not part of the lexicon of any of the parents I know. They don’t want to think about it. They don’t want to talk about it. They don’t want to know.

How irresponsible is that, and how surprising, for parents who have been so conscientious, so completely invested in their role as primary caretakers and nurturers of their children.

It’s the privileged parents to whom I address myself most fervently. Parents who put so much time, energy and money into the task of raising their children, and do so with all their intelligence, responsibility and good will. Parents who often have extra money to put towards a winter vacation someplace warm, or a summertime break by the beach. Parents who are happy to send their kids to specialty camps in the summer, and who come up with the cash for school trips, afterschool lessons, an educational weekend in the city, a junior year abroad.

It’s the privileged parents to whom I address myself most fervently. Parents who put so much time, energy and money into the task of raising their children, and do so with all their intelligence, responsibility and good will. Parents who often have extra money to put towards a winter vacation someplace warm, or a summertime break by the beach. Parents who are happy to send their kids to specialty camps in the summer, and who come up with the cash for school trips, afterschool lessons, an educational weekend in the city, a junior year abroad.

Privileged parents, listen up! If you continue to turn a blind eye to the intertwined issues of environmental degradation and climate change, both of which are caused above all by enforced, ruthless economic growth based on the heedless consumption of fossil fuels and distribution of chemicals in the water, earth and air, your beloved children will face a future in which they cannot thrive.

A future in which none of us can thrive, unless it be perhaps the cockroaches, the ants and—for a while at least—scavengers like vultures and crows.

There have been so many disaster movies produced in the past few years—The Day After Tomorrow, 2012, WALL-E—putting out on the big screen our fears about what kind of future awaits us in an age of climate crisis and ecological collapse. These movies represent our collective unconscious talking to us, presenting worse-case scenarios so that we can prepare ourselves for what may come.

There have been so many disaster movies produced in the past few years—The Day After Tomorrow, 2012, WALL-E—putting out on the big screen our fears about what kind of future awaits us in an age of climate crisis and ecological collapse. These movies represent our collective unconscious talking to us, presenting worse-case scenarios so that we can prepare ourselves for what may come.

We seem to like these movies because they give us the pleasure of stepping back afterwards and reassuring ourselves that it was just fantasy, not real.

The reports of the International Panel on Climate Change have none of the glamour of the big screen. But they are saying the same thing as those disaster pictures. They paint the same picture in different language.

It turns out that those disaster scenarios are real.

Sit with that knowledge for a bit, and then check in with yourself as a parent. Once you accept that the looming environmental crisis is real, how can you continue to live your life blithely as though everything is OK?

Parents above all have a responsibility not just to take this knowledge seriously, but to act on what we know. And parents of privilege–the 10%, the 25%–most of all.

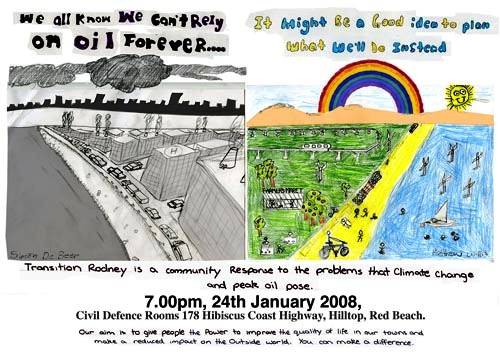

We should be vehemently protesting the poisoning of our food, air and water. We should be doing our utmost to stop the corporations who are wreaking this havoc, to change our own participation in the system, and to envision and manifest a better society that engages sustainably with the planetary ecological systems upon which we all depend.

Never before have we stood at such a juncture as a species. Now is the tipping point. Now is the time for us to stand up and be counted. Now is the time for us to dare to take a path less traveled, to think for ourselves, to do what’s right for us and our children and the world we live in, before it’s too late.

It will not be easy, the road ahead. There is so much to be done to turn this environmental train wreck around, and so little time. We may not succeed.

But we cannot continue to play dumb any more. We cannot continue to keep playing the game as if nothing were wrong, as if the biggest crisis of the past 10,000 years of human history were not on the horizon. We cannot keep dancing to the band on deck as the iceberg looms before us.

There is too much at stake, for ourselves and especially for our children, whose lives—with any luck, and a lot of hard work—will reach further into the 21st century than ours. If we care about our world—if we care about our children—we must act decisively, do whatever it takes. Now.