As I slept on my last post, the ominous words “civil war” kept resounding discordantly in my mind.

Am I really advocating for civil war? Me? I’m so non-violent I won’t even let my kids bring an x-box or a Wii into the house, for fear they might play violent video games. I’m so non-confrontational that when I get angry I get quiet, not loud. I find violence of all kinds so abhorrent that probably the only thing that would get me enraged enough to fight back is, precisely, violence, especially if visited on the defenseless: animals, children, trees.

But leavergirl‘s comment this morning has got me thinking again.

She says: “We don’t have to toughen up, but we do have to get more cunning. No street demonstrations will bring a better world. Such things force surface changes with more or less the same problems underneath. The system knows how to coopt, and knows it very well. What will bring about a better world? Living the changes at the local level.

“It’s mindboggling that people think they can “force” changes via demonstrations and protests. After all, the people in power don’t know how, even if they wanted to. We all have to invent it as we go!”

Just as it doesn’t make sense to try to fight big money with more money, it doesn’t make sense to fight violence with more violence. And she’s right that change has to happen at the local level–that is the whole “be the change” idea.

But can we afford, in this age of globalized capital and planetary climate change, to focus locally and ignore what’s happening on the national and global scale?

It seems to me that we have to do both. We have to do our utmost in our own homes and backyards and town centers to push for the principles we believe in. But we also have to keep an eye on the big picture, and add our voices to the chorus calling for a change in the grand narratives that drive social policy in boardrooms and legislative chambers.

Standing up and being counted in a protest does matter. Voicing public dissent to master narratives, as I’ve been doing in this blog, also matters. Practicing non-violence and respect in one’s home and community is also important. That’s what the fourth point in my Manifesto is about:

4. Model egalitarian, collaborative, respectful social relations in the private sphere of the family as well as the public spheres of education, the profession, government and law.

Thoreau’s model of civil disobedience, like Gandhi’s and Martin Luther King’s high-minded non-violence, were effective tactics of resistance that had real, tangible results.

So no, I am not advocating for civil war. I don’t want to see it come to that. I am, however, saying that we cannot afford to sit back and hope for the best, or wait and see, or let others worry about it. We just don’t have that luxury anymore.

I look around me and see so many of my friends who are parents investing so much time, energy, thought and care in the raising of their children. We worry over every test score, we make sure they eat their organic vegetables, we carefully shield them from violence and pain.

How can we be so focused on the local care of our children that we miss the big picture, which is that the world we will soon be sending them out into is in crisis? How can we not take it as part of our parental duty to do all we can to ensure that when our children grow up, their planet will be intact and able to support them?

On New Year’s Day I had a conversation with my son that keeps ringing in my ears this week. He expressed his anger at previous generations (including me, of course) who have so degraded our environment that as he now looks out into his own future, he cannot be sure that he will have any chance of realizing his dreams.

We talked about possible future scenarios, including one that seems to be coming up in various conversations lately: conditions of scarcity leading to armed gangs marauding in the streets and taking whatever they can find. “We would be fucked,” he said bitterly. “We don’t even have a gun in the house!”

There it is again. Would having a gun in the house make us any safer? Isn’t the problem precisely that there are too many guns in too many houses?

And is it inevitable that conditions of scarcity would lead to violence? Maybe it’s likely, but are there steps we can take now to promote a different outcome?

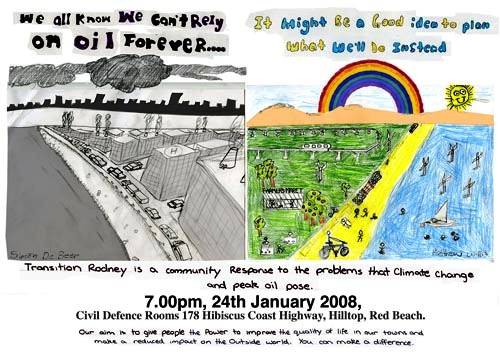

Back to the importance of the local. Strengthening local communities can head off a dog-eat-dog mentality. We are all in this together. Together, we created the present moment we now stand on; and together we will create the future.

What future do we want? We all want abundance; peace; stability; security. I don’t think anyone in the world would argue with those general goals.

We have the knowledge and the technology, right now, to achieve these goals, worldwide.

We do! If we turned our best and brightest minds to the task, we could drastically reduce our carbon emissions within a decade, while still enjoying electricity and heat through solar, geothermal and wind. We could drastically improve energy efficiency and get rid of our wasteful consumerist mindset. We could stop making bombs and missiles, and instead refocus those trillions of dollars into education and social welfare, including intensive sustainability efforts on all fronts.

We could do this. But again, we need that unstoppable groundswell of demand for change. Locally and globally. NOW.