The recent Presidential election showed in concrete terms that the demograhics of the United States are shifting quickly. The old majority of people of European descent (“Caucasians”) is rapidly shrinking to minority status in numerical terms, although white folks retain a lock on the gears of power and privilege so far in this country.

How do white folks continue to maintain dominance?

The key is still education.

When my Eastern European Jewish forebears came to the US through Ellis Island back at the turn of the 20th century, the adults in the family spoke no English, but they were hardworking and ambitious for their children to assimilate and succeed.

One of my great-grandfathers fixed sewing machines on the Lower East Side; another great-grandmother sold fish wrapped in newspaper on the street to support her children.

Within a generation, the children of these immigrants were living the middle-class American dream, and their children did even better, becoming doctors, lawyers, teachers and professionals.

My grandmother, a first-generation American whose mother tongue, before entering kindergarten, was Yiddish, got her B.A. and Masters in biology from Hunter College, and became a high school biology teacher. Her son, my father, graduated from Oberlin and NYU and became a successful professional. I followed the pattern and got my Ph.D.

This is what’s known in Americanese as pulling oneself up by the bootstraps.

What is too often unacknowledged is how the privilege accorded to whiteness in America has helped families like mine succeed.

It starts with where you are able to live, because property taxes still determine the quality of the primary and secondary education you’ll receive.

In the first half of the 20th century, there were a lot of places in the U.S. where Jews weren’t welcome, including many selective colleges and universities.

But just like the Irish and the Italians, soon enough Jews became “white,” and that was all that mattered—they were welcome in all but the snootiest bastions of American WASP-dom, and their privileges were helped along by the exclusion of others.

The color of one’s skin still matters in this country. We still live in largely segregated neighborhoods, and thus most of our children attend largely segregated schools.

And they’re not “separate but equal” schools either. They are, as Jonathan Kozol so eloquently documented, deeply unequal schools, where children with darker skin tones—who are often the most in need of support–are given less, financially and intellectually.

The fight over “race-blind” college admissions is so fraught because what tends to happen without any affirmative action policy for Americans of color is that the people with the best “grooming” win out, and the best-groomed high school seniors tend to be those from affluent families, living in affluent neighborhoods, going to affluent schools.

As The New York Times noted in a recent editorial, “Those from the top fifth of households in income are at least seven times as likely to go to selective colleges as those in the bottom fifth. The achievement gap between high- and low-income groups is almost twice as wide as between whites and blacks,” and “blacks and Hispanics are also substantially underrepresented at selective colleges and universities. In 2004, they were 14.5 percent and 16 percent, respectively, of those graduating from high schools, but only 3.5 percent and 7 percent of those enrolling in selective colleges and universities. The underrepresentation has gotten worse over the past generation.”

***

All this is on my mind today because of a recent stir at the college where I teach, which has made a strong effort over the past decade to recruit more students from under-represented groups.

We have more people of color on the campus today than we’ve ever had, which should be a cause for celebration.

But this semester has brought some simmering tensions to the surface, showing how difficult it can be to put a group of passionate young people together on a campus and expect them to “just get along.”

The flashpoint this semester was Diversity Day, a day started several years ago by a group of disgruntled students who felt that not enough time was spent during regular classes focusing on issues of social diversity.

Students, staff and faculty organized workshop classes on a range of topics related to the experience of marginalized groups in America, and theories and praxes of social justice.

The day was so successful that it was subsequently institutionalized, with regular classes cancelled and all students required to attend at least three workshops.

This year, an influential group of students decided they were going to “boycott” Diversity Day. Many of them were the student leaders of workshops, which meant that they were actually sabotaging their own event.

They took this extreme measure because they were angry at what they perceived as a lack of strong response from the college administration to the provocation of a student who questioned not just the value of diversity day, but the value of diversity itself in American society.

This student distributed posters on campus asking students to “Take the Diversity Challenge” by answering the following question: “Name 5 benefits of Diversity (besides ethnic food and music).”

His challenge was taken as a white supremacist assault on students who wear the mantle of diversity with pride, and he did not do much to dispel that perception, according to students who said he also sent them a link to a You-Tube talk by Jared Taylor, the controversial founder of the New Century Foundation and editor of its American Renaissance magazine.

The anti-discrimination watchdog organization Southern Poverty Law Center, which keeps tabs on Taylor, says that he “regularly publishes proponents of eugenics and blatant anti-black and anti-Latino racists,” and also “hosts a conference every other year where racist intellectuals rub shoulders with Klansmen, neo-Nazis and other white supremacists.”

In the video link shared on our campus, Taylor argues that because there is often friction when you put different social groups into close proximity (and he’s especially attentive to different racial groups)—say, in neighborhoods or schools or college campuses—the better thing to do is to back away and re-segregate, thereby eliminating the sources of tension.

This attitude is wrong on so many levels that I find it hard to know where to start.

Besides the obvious truth that race is just an illusion, as far as a real biological marker of human difference, it’s also true that ghetto-izing certain individuals, for whatever reason, has never been a good social strategy in the past, and it won’t work now.

We don’t want a balkanized, fearful, hateful America any more than we want a bland, homogenized America.

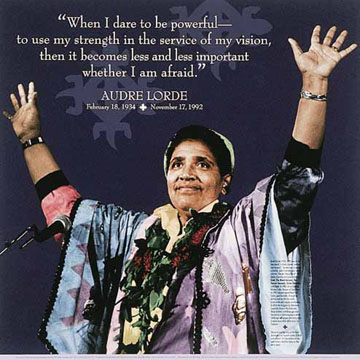

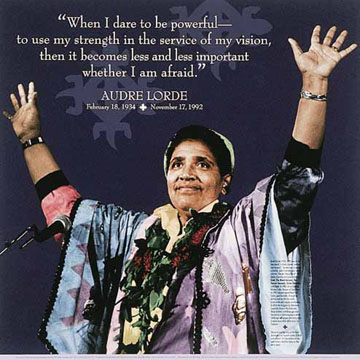

We want a society where, as Audre Lorde put it, “difference [is] not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic.”

In her famous essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Lorde continued: “Within the interdependence of mutual (nondominant) differences lies that security which enables us to descend into the chaos of knowledge and return with true visions of our future, along with the concomitant power to effect those changes which can bring that future into being” (Sister Outsider, 111-12).

***

Audre Lorde

At my college, we like to say that we teach “critical thinking skills,” by which we mean that we encourage students to question authority and think for themselves.

We shouldn’t be surprised or upset, then, when they do just that by questioning our own institutional authority.

The students who organized the Diversity Day boycott this year—many of them women of color–were angry that a student advocating white supremacy was allowed to remain in our campus community.

While the administration deliberated over whether this student presented any danger to the community, and whether his words had crossed the line into hate speech, they said, they felt unsafe and unheard.

So they staged a protest, quite in keeping with Audre Lorde’s injunction to “transform silence into language and action.”

“I have come to believe,” Lorde says, “that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood.” She urges her readers to ask themselves “What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence? ….We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and our selves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid” of speaking out.

But, she continues, “We can learn to work and speak when we are afraid in the same way we have learned to work and speak when we are tired. For we have been socialized to respect fear more than our own needs for language and definition, and while we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us….

“It is not difference that immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken” (“The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” Sister Outsider, 41–44).

On our campus, Diversity Day originated as an attempt to break the silences between different social groups, including students, faculty and administration, in the cause of mutual understanding and communication.

But this year, it was the boycott that spoke loudest, and what it said, loud and clear, was that there are still so many silences to be broken.

Speaking as a faculty member who teaches classes in human rights and social justice, and who has organized many Diversity Day workshops over the years, the problem is that it’s often too little, too late.

By the time Diversity Day rolls around in November, tensions between social groups on campus have often already come to the fore, and the workshops provide opportunities to let off steam that can end up sparking further conflagrations that take place in the dorms or on social media sites, without the mediating influence of faculty and staff present to help channel discussions productively.

One day out of the school year is not enough to create the social bonds necessary to establish a cohesive, harmonious diverse student body.

We are going to have to try harder, to do better.

***

An opening has been created for us by the students this year. From my perspective as a faculty member, this is a prime teachable moment, an opportunity to advance our ideals of social justice and strengthen the ties of community on our campus.

Those with more privilege, on whatever grounds, must stand as firm allies with the less privileged.

Every class, every conversation, every interaction is an opportunity for respectful communication that encourages the breaking of the deep-seated silences that separate us.

The truth is that every college campus is a microcosm of the larger society from which our students are drawn. In the small, sheltered community we create—a kind of Beloved Community, in Martin Luther King Jr.’s terms—we have an opportunity to envision and manifest new frameworks and understandings that our students will then carry with them out into the broader world.

In this struggle, as in all others, we are the ones we’ve been waiting for, and the time for thoughtful action is now.

I don’t have TV in the house, so I got most of my information on the situation in Boston from print media and radio. But even the few pictures I saw were enough to convey the sense that the official response to these boys’ stupid act of random violence was hugely disproportionate.

I don’t have TV in the house, so I got most of my information on the situation in Boston from print media and radio. But even the few pictures I saw were enough to convey the sense that the official response to these boys’ stupid act of random violence was hugely disproportionate. Not only is the U.S. the largest exporter of arms and weaponry in the world, but we are also the biggest developer of violent video games worldwide, the ones I am betting those Chechen boys loved to play.

Not only is the U.S. the largest exporter of arms and weaponry in the world, but we are also the biggest developer of violent video games worldwide, the ones I am betting those Chechen boys loved to play.