I shouldn’t be surprised that once again the ugly specter of racism and unacknowledged privilege is raising its head on my own little campus community.

It happens almost every year like clockwork, generally in the fall semester around this time, and usually involving freshmen who are still in the process of adjusting to the new, often more racially/ethnically/socially diverse culture in which they have suddenly landed.

Understandably, people of color who have had to put up with racism and white privilege all their lives get angry when it turns up, in all its crude arrogance, here in our campus home as well.

One angry response leads to another angry retort, onlookers begin to take sides, and before you know it the campus is in an uproar, with some calling for apologies, others calling for calm, and the majority just plain mad and not willing to take it anymore.

I want to talk about anger.

As a woman, albeit a white woman, I know something about how members of subordinate groups are not supposed to respond with anger to actions by members of dominant groups. We are supposed to keep our cool, to turn the other cheek, seek the higher ground, not stoop to their level.

So we pretend we didn’t hear that cutting remark, muttered just loud enough to be audible. We pretend we didn’t want to go to that party anyway—the one to which our invitation somehow got lost in the mail. Above all, we don’t respond directly to provocation, because that will just give them an excuse to keep going, and make the whole situation worse—not for them, but for us.

So the anger, unexpressed, gnaws at us, sitting in the pit of our stomachs as unmetabolized bitterness that threatens to choke us when, at unexpected moments, its bile rises into our throats.

Audre Lorde

As a woman, I have felt this bitter resentment. And yet as a white woman, I have also felt the other side, the ignorant innocence of privilege. Growing up in a racist society, I did, as Audre Lorde famously put it, accept racism “as an immutable given in the fabric of [our] society, like eveningtime or the common cold” (“The Uses of Anger,” Sister Outsider, 128).

I didn’t think to question why there were no African American families living in my apartment building on the Upper East Side of Manhattan—other than, of course, the live-in maids who could be seen going in and out of the service entrance or trundling laundry down the service elevator. None of the doormen or elevator men were people of color either—most were Irish, like our superintendent, or perhaps German or Scandinavian.

I didn’t think to question why there were hardly any African Americans or Latinos in my public elementary school, or in the selective public high school I attended, Hunter College High School. When I got to college, it was the same, and again, I was incurious, complacent.

When you grow up this way, in an insular environment of privilege, it is possible to be deluded into thinking that this is just the way the world is. No one in my whole upbringing encouraged me to ask the kinds of questions that might have made me see the how the fabric of my existence was shot through with deep-seated, longstanding racism. No one talked about it. It just was, and since for me that privileged life was very comfortable, I had no incentive to rebel against it.

It was reading that eventually opened my eyes to how the other half (or, globally speaking, two-thirds) lives.

When I happened upon Lorde’s autobiography, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, and read about how she too had gone to Hunter College High School, the only Black girl in a sea of white, and how hard that was for her in so many ways, I began to see my experience there through her outsider’s eyes. I began to question the way I had lived in a vacuum of privileged blindness for so long.

Lorde’s essay on “The Uses of Anger” is one I go back to again and again. The sentence that continues to resonate powerfully with me is this:

“I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own” (132).

Listening to Audre Lorde with an open heart, I understood why she was angry at the racist structures into which she was born and bred. I knew I was not responsible for creating those structures, into which I too had been born and bred, but I did have the power to question them, and to ally myself with those who were working to change them.

When it comes to racism and other forms of identity-based oppression, it really is true that ‘you’re either with us or against us.” There’s no way to hide behind a façade of neutrality. To say nothing when someone drops a racial slur or pinches a woman’s behind is to become an accomplice to that act. In these situations, silence is itself a form of tacit consent.

Audre wrote about that too, in an essay called “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.”

I often reread these lines when I am feeling fearful of speaking out on an issue I care about:

“We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and our selves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners as mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid….We can learn to work and speak when we are afraid in the same way we have learned to work and speak when we are tired. For we have been socialized to respect fear more than our own needs for language and definition, and while we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us….it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken” (42-44).

As an ally with some measure of privilege, one of the best things I can do to advance the goal of a just society is to speak up when I see racism or sexism or any other form of discrimination taking place. And not just speaking to my friends, but speaking up in public, inviting and sometimes even provoking a sustained conversation, with the aim of promoting greater awareness and understanding.

The flashpoint for the current unrest on my campus was a white male student challenging the validity of the school holding a campus-wide teach-in known as “Diversity Day,” in which students, staff and faculty organize workshops around issues related to the politics of identity. Originally, Diversity Day was entirely a student-organized event, held on an extracurricular basis to compensate for a perceived lack of attention to non-white-western-male culture and experience in the curriculum. The founding students lobbied hard, and ultimately successfully, to have their effort institutionalized by having classes cancelled, with all students required to attend at least two workshops during the day.

Whenever a revolutionary gesture becomes institutionalized, it loses some of its spark, and maybe this is an event that needs to continue to evolve.

But only someone who was ignorant of the extent to which discrimination and structural identity-based limitations continue to affect women and people of color in this country could argue in good faith that it was not worthwhile to spend some time discussing these issues one day out of the school year.

Of course, many students will take classes in sociology, anthropology, gender studies or ethnic studies and go a lot deeper. But those are often the students who already have an inkling that all is not well for subordinate groups.

It is the most privileged who are often the least aware of how systems of privilege operate, and therefore the least likely to elect to take classes in these topics. These are the students who are most likely to benefit from being required to attend two eye-opening workshops on Diversity Day.

At many of these workshops, people of privilege will be asked to confront W.E.B. Dubois’s famous question in The Souls of Black Folk, “How does it feel to be a problem?”

Robert Jensen

Robert Jensen, one of the finest anti-racist, anti-sexist writers and educators I know, says that in the 21st century, “the new White People’s Burden is to understand that we are the problem, to come to terms with what that really means, and act based on that understanding. Our burden is to do something that doesn’t seem to come naturally to people in positions of unearned power and privilege: Look in the mirror honestly and concede that we live in an unjust society and have no right to some of what we have” (Jensen, The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism and White Privilege, 92).

The next step, he says, is to “commit to dismantling white supremacy as an ideology and a lived reality”—not because it’s hurting other people, but because, as Lorde recognized, “none of us is free while some of us are still shackled.”

Or, as Alice Walker put it, “We care because we know this: The life we save is our own.”

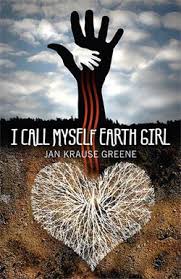

For the past few nights I have been putting myself to sleep by reading an advance copy of my friend Jan Krause Greene’s new novel, I Call Myself Earth Girl.

For the past few nights I have been putting myself to sleep by reading an advance copy of my friend Jan Krause Greene’s new novel, I Call Myself Earth Girl.