In many thoughtful circles around the world, Eckhart Tolle is a familiar figure. His philosophy is encapsulated in the title of his first book, The Power of Now: it’s about the importance of living in the present, as opposed to the future and the past. Having gotten that far in his thinking, it seemed simple enough, and I didn’t bother to read the book; nor did I pick up his latest book, A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose, although I was intrigued by the connection in the title between individual realization and changing the world. Was he giving us a new version of the old adage “Be the change you want to see?”

In many thoughtful circles around the world, Eckhart Tolle is a familiar figure. His philosophy is encapsulated in the title of his first book, The Power of Now: it’s about the importance of living in the present, as opposed to the future and the past. Having gotten that far in his thinking, it seemed simple enough, and I didn’t bother to read the book; nor did I pick up his latest book, A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose, although I was intrigued by the connection in the title between individual realization and changing the world. Was he giving us a new version of the old adage “Be the change you want to see?”

Still, I gave it a miss until my brother, a businessman who generally has had little use for mystical reflection, began talking it up and telling me it was a must-read, that it had really made him think and act in new and positive ways. So I brought A New Earth with me to Nova Scotia, and read it immediately following Mark Hertsgaard’s Hot.

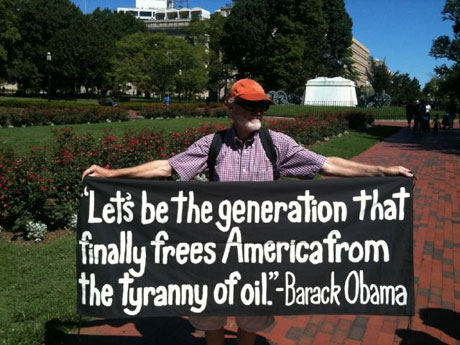

No two books could be more different. Hertsgaard is also talking about “a new Earth,” but his focus is on changing external reality: shifting from fossil fuels to renewables, building dykes and levees against rising waters, winning over hearts and minds so that more people commit to the struggle to keep global warming from getting to the catastrophe point, which, Hertsgaard reminds us constantly, is not far away.

Tolle, on the other hand, is entirely focused on changing internal reality: changing the way we human beings think and experience our lives. He believes that collectively, human thought patterns can affect the external world.

“The dysfunction of the egoic human mind, recognized 2,500 years by the ancient wisdom teachers and now magnified through science and technology, is for the first time threatening the survival of the planet….A significant portion of the earth’s population will soon recognize, if they haven’t already done so, that humanity is now faced with a stark choice: evolve or die” (21).

Tolle spends a lot of time in the book explaining what he means by “the egoic mind.” Basically, it’s the competitive, material, greedy, selfish human mindset: the mindset that gave rise to brutal colonialism and exploitative capitalism; that corrupted Marx’s concept of communism into Stalinism, Maoism and Castroism; the mindset that has categorized, subordinated and persecuted people based on their skin color, religion or ethnicity; that has made the last 5,000 years a non-stop series of wars, and has steadily exterminated millions of species on this planet.

For Tolle, it’s not a matter of shifting to some new ideology—it goes much deeper than that. “What is arising now is not a new belief system, a new religion, spiritual ideology or mythology. We are coming to the end not only of mythologies but also of ideologies and belief systems. The change goes deeper than the content of your mind, deeper than your thoughts. In fact, at the heart of the new consciousness lies the transcendence of thought, the newfound ability of rising above thought, of realizing a dimension within yourself that is infinitely more vast than thought” (21).

This dimension within us seems to be what mystics throughout the ages have tried to name—it has gone by names like “the soul,” “the spirit,” “the divine,” representing our connection to something greater than our limited human bodies. Tolle’s methods of accessing this “new consciousness” are familiar to anyone who has even a passing knowledge of Buddhism, and indeed he draws frequently on references from Buddhist thinkers, from Siddhartha on down. Meditate; focus on the present moment, using the breath as an anchor; when your thoughts wander to past or present, bring them back gently but firmly to the present. Be comfortable with uncertainty; don’t insist on limiting self-definitions; drop the habitual role-playing and be authentic with everyone you meet. Stop focusing on negative emotions, pain and violence. Recognize your fundamental connection with all-that-is, and stop trying to control everything.

Tolle calls unhappiness “a disease on our planet” (213). The only way for us to become happier as a species, which will automatically translate into a more balanced and sustainable future for our planet as a whole, is for humans to come to “accept the present moment and find the perfection that is deeper than any form and untouched by time. The joy of Being, which is the only true happiness, cannot come to you through any form, possession, achievement, person or event—through anything that happens. That joy cannot come to you—ever. It emanates from the formless dimension within you, from consciousness itself and thus is one with who you are” (214).

OK, the skeptic in me says—sounds good, Eckhart, but do you really want me to believe that if all 7 billion of us were to start meditating and finding our inner Being, which is to say our connection with the source energy that animates our planet and our universe, we could undo the millennia of human destructiveness, including the current climate challenges?

On the other hand, isn’t that what materialists like Hertsgaard and McKibben are talking about too—recognizing how humans are an integral part of the ecological web of our planet, and acting out of this awareness? We are not here to dominate and exploit the planet, we are here to play our parts in the great dance of life.

Cruelty, hatred and willful, excessive destruction are uniquely human—we are the only beings on this planet that engage in this kind of negative behavior. Eckhart Tolle is right that there are more and more people arising now who recognize this behavior for the sickness it is, and are changing—starting with themselves, and moving out into the world.

Tolle’s great insight is that if we were to allow ourselves to connect with the source energy of the planet—the divine spark, the soul, the spirit that animates us and our world—we would become incapable of cruelty and brutality. We would have evolved to another level of consciousness. Tolle is clear about this: we must evolve, or die out as a species.

On an individual level, there do seem to be growing numbers of people out there who recognize our fundamental connection to the web of life, and the need to change our ways of living to bring ourselves into a harmonious relationship with our environment. However, on a larger societal level, we remain imprisoned by old structures that arose in the 18th and 19th centuries, and keep us treading the same old destructive rut. Property rights, human superiority over animals, human comfort and consumption as an unquestioned priority, the profit imperative, the recourse to violence as a response to any challenge…all these old structures (Tolle would call them “thought-forms”) are then supported and strengthened by laws and political systems developed ages ago, that keep us knotted firmly into place.

We may be able to change individually, but how will these structures change? History has shown that major changes like constitutional amendments, national boundaries and systemic political overhauls have come about only through violence and upheaval. Can it really be that this time the collective power of enough of us sitting around focusing on the present and finding our inner connection to Being will do the trick?

Certainly I agree with Tolle that we would be happier if we lived more in the present moment, and were motivated by the joy of Being, rather than the egoistic desire for fame and fortune. I just wonder whether we might get so lost in meditating that we fail to notice the tsunami that’s about to sweep us away. Or maybe that is still being too old-school: worrying about the future, and failing to realize that the end of our human body is not a cause for grief, but rather a return to the energetic source of our planet, a cause for celebration.

Hmmm.

Meanwhile, up in another part of New York, I was at a conference this weekend celebrating “40 Years of Feminist Activism and Scholarship” at the Barnard Center for Research on Women. Here all was decorous and polite–no protesters, no cops, no tight handcuffs or people being pulled down the sidewalk by their feet.

Meanwhile, up in another part of New York, I was at a conference this weekend celebrating “40 Years of Feminist Activism and Scholarship” at the Barnard Center for Research on Women. Here all was decorous and polite–no protesters, no cops, no tight handcuffs or people being pulled down the sidewalk by their feet. Fortunately, the panel I had organized, on “Living and Working in the Borderlands,” was up next, and it kicked us in to a whole different register. Margaret Randall read poetry that wrenched us into the heart of the dangerous, shifting borders between past and present, safety and terror, life and death.

Fortunately, the panel I had organized, on “Living and Working in the Borderlands,” was up next, and it kicked us in to a whole different register. Margaret Randall read poetry that wrenched us into the heart of the dangerous, shifting borders between past and present, safety and terror, life and death. I’ll end with the voice of a martyr for political freedom, Victor Jara, savagely murdered by the Chilean goon squad while still valiantly trying to sing his songs of peace:

I’ll end with the voice of a martyr for political freedom, Victor Jara, savagely murdered by the Chilean goon squad while still valiantly trying to sing his songs of peace:

Josh Haner/The New York Times)

Josh Haner/The New York Times)