There is a clear spectrum of response to the urgency of the environmental and economic challenges that face us.

On the one end is the Deep Green Resistance movement, calling for a complete take-down of industrialized civilization, violently if necessary (and it would be necessary, of course–industrial civilization won’t go down without a fight, unless it’s wiped out by natural disasters).

On the other end are those who believe we will be able to find our way into a sustainable world order via technology, ie, renewable energy sources that will keep the capitalist engines burning bright.

On this spectrum, I would have to locate myself somewhere in the middle. While I see the necessity of deindustrialization, I don’t really want to live through the violent havoc a strong de-civ movement would cause.

But I know things can’t go on as they have been. We must shift from an economic model built on endless growth to one that seeks to maintain a steady state, both for human societies and for the natural world (as if there were a separation between these two).

We must also shift from the capitalist system of accumulated wealth for the few based on the commodified labor of the masses, to a system in which people’s labor is more directly connected to their well-being, and wealth is not allowed to concentrate in a few disproportionately powerful, distant hands.

The only movement I’ve found so far that is actively working to accomplish a vision similar to what I’ve sketched out above is the Transition Town movement. The brainchild of UK visionary activist Rob Hopkins, the movement describes itself as follows:

The only movement I’ve found so far that is actively working to accomplish a vision similar to what I’ve sketched out above is the Transition Town movement. The brainchild of UK visionary activist Rob Hopkins, the movement describes itself as follows:

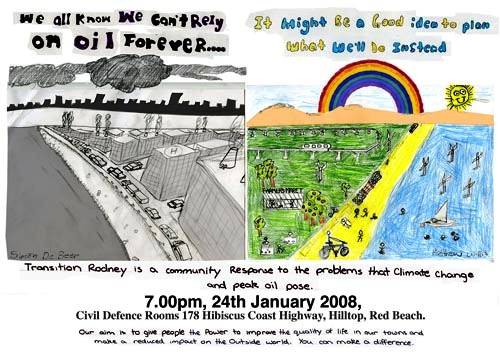

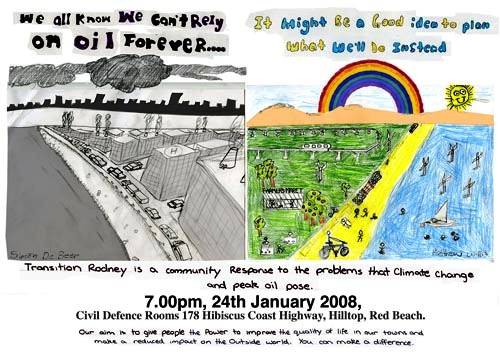

“The Transition Movement is comprised of vibrant, grassroots community initiatives that seek to build community resilience in the face of such challenges as peak oil, climate change and the economic crisis.

“Transition Initiatives differentiate themselves from other sustainability and “environmental” groups by seeking to mitigate these converging global crises by engaging their communities in home-grown, citizen-led education, action, and multi-stakeholder planning to increase local self reliance and resilience.

“They succeed by regeneratively using their local assets, innovating, networking, collaborating, replicating proven strategies, and respecting the deep patterns of nature and diverse cultures in their place.

“Transition Initiatives work with deliberation and good cheer to create a fulfilling and inspiring local way of life that can withstand the shocks of rapidly shifting global systems.”

What appeals to me about the Transition Town movement as a strategy for change is that it’s locally based and collaborative. The first step is getting to know your neighbors, finding out what skills you can share, and taking stock of how you can prepare intelligently to cope with whatever environmental and economic shocks may lie ahead in our future. It doesn’t dictate a one-size-fits-all model, but rather gives communities credit for being smart enough to figure out their own, locally adapted solutions.

As a society, America seems to be in collective denial about the reality of climate change. We don’t want to hear that if we continue down the path of capitalist growth based on fossil fuels, the planet will heat up past the point where we could expect life as we know it to continue. We don’t want to put the pieces together, because if we do, we will be forced to face the fact that we need to change.

If we could accept this fact, we could begin to talk seriously about directions to take to make that change happen. It would be nice if we could count on our world leaders to step up and face the challenge squarely, in a concerted effort. But given the reality of global politics, still based on competition and armed power struggles, it seems very unlikely that we can look to the United Nations, or individual national governments, for the kind of decisive leadership we need now.

So we need to turn to each other, on the local level, and begin asking, as the Transition Town movement envisions, what can we do right here, together, to become more resilient? What resources do we have, right here, that are not dependent on current systems of international or long-distance national trade? How can we plan together for a sustainable future?

In a way, it’s an effort to de-couple our personal wagons from the locomotive of capitalist growth, which is proving so destructive to everything in its path, and seems to be on the verge of careening out of control.

I’ve been hearing a fair amount of fear expressed about “going backwards.” When people imagine stepping down from the capitalist growth model, they picture having to give up modern conveniences like advanced medical technologies, ready access to electricity, indoor plumbing, etc.

It doesn’t have to be that way. We have to work on developing new ways of generating those conveniences, that are less destructive to the planet (the technological fix) and also work swiftly to dismantle those features of industrial civilization that are throwing our whole ecological system out of balance (de-industrialization).

The Transition Town movement calls this “the great re-skilling” approach. We need to remember older, more sustainable ways of doing things, while also keeping the best of new technologies and learning how to apply them in smarter, more efficient and ecologically sound ways.

There are over 100 full-fledged Transition Town initiatives in the U.S., and hundreds more worldwide, along with many start-up groups forming all the time. Although all of us seem to have so much to do, and so little time these days, this is really a movement we need to be focusing on now to prepare for the decade ahead.

Given the lack of effective top-down leadership, should we really be wasting our time worrying about national elections, for example? Or bothering to go to international conferences on climate change?

Or is the smarter thing to do to begin, quietly and with determination and hopeful good cheer, to make our own preparations for a very different sort of future, in our own transition towns?