Once again we are seeing how the democratic power of social media can thwart the efforts of the state political apparatus to keep the people in line.

This time it’s happening in Indian Country, beginning in northernmost Canada and spreading like wildfire through social media networks down south and out into the broader world.

The movement is called Idle No More, and it was started by a coalition of four indigenous and non-indigenous women from Saskatchewan—Sylvia McAdam, Jess Gordon, Nina Wilson and Sheelah Mclean—who decided last fall that enough was enough with the steady assault on the environment and protections for First Nations lands in Canada.

Idle No More Founders

Taking specific aim at an omnibus bill in the Canadian Parliament, known as Bill C45, the women began teach-ins and protests around their homes in northern Canada. Word spread quickly across North America and beyond via social media channels, and a global solidarity movement was born.

Idle No More protest in Toronto last month

According to the Idle No More website, this is what happened:

Bill C45 brings forward changes specifically to the Indian Act that will lower the threshold of community consent in the designation and surrender process of Indian Reserve Lands.

Sheelah McLean reminds us that the bill is about everyone. She says “the changes they are making to the environmental legislation is stunning in terms of the protections it will take away from the bodies of water – rivers and lakes, across the country.” She further adds, “ how can we not all be concerned about that?”

The Idle No More efforts continued in Alberta with an informational meeting held at the Louis Bull Cree Nation. The organizer for that event, Tanya Kappo, took to Twitter and Facebook to help generate awareness on the matter as the passage of Bill C45 was imminent.

Kappo says, “the people in our communities had absolutely no idea what we were facing, no idea what plans Stephen Harper had in store for us.” The events leading up to the National Day of Action have been focused on bringing awareness to people in First Nations communities and the rest of Canada.

Jess Gordon says, “The essence of the work we are doing and have been doing will remain a grassroots effort, and will continue to give a forum to the voices of our people.”

When Bill C45 was brought to the House of Commons for a vote, First Nations leaders demonstrated that they are hearing these voices loud and clear. They joined the efforts against Bill C 45 and went to Parliament Hill where they were invited into the House of Commons by the New Democratic Party.

However, they were refused entry. This refusal to allow First Nations leadership to respectfully enter the House of Commons triggered an even greater mobilization of First Nation people across the country.

Nina Wilson says, “what we saw on Parliament Hill was a true reflection of what the outright disregard the Harper Government has towards First Nation people.”

With the passage of Bill C45, Idle No More has come to symbolize and be the platform to voice the refusal of First Nations people to be ignored any further by any other Canadian government.

Yesterday I happened to catch a call-in program on the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Co.) on the Idle No More protests, which have apparently taken most Canadians by surprise. The host interviewed a representative of the Canadian environmental protection agency, and it was shameful to listen to the way he sputtered when asking whether the bill in question really would result in damaged waters and fisheries.

Although he refused to come out and say it, the short answer was clearly, “Yes.”

As always, for mainstream politicians and businessmen the lure of short-term profits outweighs longterm planning for the health and welfare of the planet and her denizens.

Some of the callers on the CBC program displayed evident racism in their attitudes towards the Native peoples behind the Idle No More protests, which have blockaded railways and highways in recent weeks, in an effort to gain the attention of the Canadian prime minister, Stephen Harper.

Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence

One Native Chief, Theresa Spence, has been on a hunger strike for nearly a month now, her immediate goal simply being an audience with Mr. Harper and a chance to present the First Nations case. Harper has finally agreed to meet with Spence and other chiefs, on January 11, 2013, one month after she started her hunger strike.

Spence is a controversial figure in this movement, which began with a grassroots coalition and has displayed some reluctance to let the indigenous chiefs steal the thunder.

There have been rumors of corruption among the chiefs, including Spence herself, who has just now, conveniently enough, been subjected to a humiliating government audit of her finances.

It’s not clear whether all the chiefs are truly after the protection of the environment, or if they just want to have their fair share of the economic action when it comes to the rapid development of Canada’s northern territories.

What is clear is that the immense land and resource grab in the Americas, which began with the colonial conquests and has continued to the present day, provides short-term financial gains for the few—mostly non-indigenous corporations and financiers—while the majority of Native peoples languish in poverty, sitting on environmentally devastated lands.

Aerial view of Alberta tar sands development, aka the destruction of the Alberta boreal forest. (Global Forest Watch Canada)

In case after case worldwide, rapacious corporations sweep in, negotiate favorable leases on the land, extract the resources and move on, leaving behind a toxic, degraded landscape and a broken people.

Now we have finally come to the time when it is becoming obvious that the damage that is being wreaked on people and their environments in specific parts of the world is not just “their own problem.”

As the founders of the Idle No More movement correctly perceived, if the waters of Canada are not protected, it will affect all Canadians, not just the First Nations folk who sit closest to those waterways.

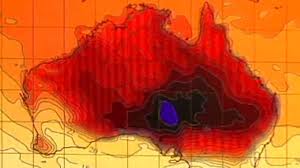

If the boreal forests of northern Canada are razed, it will affect the entire planet, just as the steady destruction of the rainforests in the southern latitudes is inexorably destabilizing our climate worldwide.

It appears that our politicians only understand the language of dollars and cents. In New York and New Jersey now, a serious discussion is underway about how to pay for the cost of adapting to the climate change that almost everyone sees now as inevitable.

Yes, we have to adapt, we have to mitigate the damage by changing the way we develop our coastlines.

But we also have to adapt our mindsets when it comes to “development of natural resources”—a green-washed euphemism for what has really been “the wholesale destruction of the planet.”

This is as true for the destruction of the boreal forests of Canada as it is for the fracking of the Marcellus Shale in the U.S.

If the real costs of this kind of destructive “development” were added up, no sane financier or politician would be able to support such a suicidal undertaking.

If our politicians and business leaders want to commit hari-kari by reckless short-term myopic thinking, good riddance to them.

But they have no right to take the rest of us along with them.

It reminds me of suicide cults like the infamous one in Jonestown, Guyana, in the 1970s. A whole group of people was so taken in by the charismatic leadership of their guru, Jim Jones, that they obeyed his order to commit ritual suicide.

Victims of the Jonestown suicide cult

In our case, it’s the entire global capitalist leadership that has us all in thrall. We have been seduced, charmed and entranced by the siren call of “development,” which has given mainstream North Americans—the ones who agree to play by the rules—the benefits of a comfortable lifestyle.

The hidden underbelly of this lifestyle—the environmental destruction, the extermination of thousands of species annually, the annihilation of entire groups of indigenous peoples worldwide, the irrevocable destabilization of our climate—is now coming into view, thanks in large part to the democratization of the media through the World Wide Web.

I continue to believe that when ordinary, good-hearted people understand their own role in this planetary destruction, they will stand up and insist, like the four women who founded Idle No More, that enough is enough.

The question is, how far will we be willing to go to insist that our leaders respect our values and stop dragging us down the road to ruin?

How far will we have to go?

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

–Margaret Mead

In the wake of the Boston Marathon bombing this week, like everyone else I’ve been thinking again about violence.

In the wake of the Boston Marathon bombing this week, like everyone else I’ve been thinking again about violence. Bombs loaded with nails and bb pellets, set off low in a dense crowd, are calculated to inflict maximum damage on soft exposed flesh and limbs.

Bombs loaded with nails and bb pellets, set off low in a dense crowd, are calculated to inflict maximum damage on soft exposed flesh and limbs.