“Organic, schmorganic,” fumes New York Times columnist Roger Cohen sarcastically in an article entitled “The Organic Fable.”

He bases his sweeping dismissal of the organic foods movement on a new Stanford University study claiming that “fruits and vegetables labeled organic are, on average, no more nutritious than their cheaper conventional counterparts.”

Cohen does grant that “organic farming is probably better for the environment because less soil, flora and fauna are contaminated by chemicals…. So this is food that is better ecologically even if it is not better nutritionally.”

But he goes on to smear the organic movement as “an elitist, pseudoscientific indulgence shot through with hype.

“To feed a planet of 9 billion people,” he says, “we are going to need high yields not low yields; we are going to need genetically modified crops; we are going to need pesticides and fertilizers and other elements of the industrialized food processes that have led mankind to be better fed and live longer than at any time in history.

“I’d rather be against nature and have more people better fed. I’d rather be serious about the world’s needs. And I trust the monitoring agencies that ensure pesticides are used at safe levels — a trust the Stanford study found to be justified.”

Cohen ends by calling the organic movement “a fable of the pampered parts of the planet — romantic and comforting.”

But the truth is that his own, science-driven Industrial Agriculture mythology is far more delusional.

Let me count the ways that his take on the organic foods movement is off the mark:

- Organic food may not be more “nutritious,” but it is healthier because it is not saturated with pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and preservatives, not to mention antibiotics, growth hormones and who knows what other chemicals. There are obvious “health advantages” in this, since we know—though Cohen doesn’t mention—that synthetic chemicals and poor health, from asthma to cancer, go hand in hand.

- Organic food is only elitist if it comes from Whole Foods—the one source Cohen mentions. I grow organic vegetables in my backyard, and they save me money every summer. We don’t need the corporatization of organic foods, we need local cooperatives (like the CSAs in my region) to provide affordable organic produce that doesn’t require expensive and wasteful transport thousands of miles from field to table.

- About feeding 9 billion people: first of all, we should be working hard to curb population growth, for all kinds of good reasons. We know we’ve gone beyond the carrying capacity of our planet, and we shouldn’t be deluding ourselves that we can techno-fix our way out of the problem. Industrial agriculture is a big part of the problem. It will never be part of the solution. Agriculture must be relocalized and brought back into harmony with the natural, organic cycles of the planet. If this doesn’t happen, and soon, all the GMO seed and fertilizers in the world won’t help us survive the climate cataclysm that awaits.

- Mankind is better fed and longer lived now than any time in history? Here Cohen reveals his own elitist, Whole-Foods myopia. Surely he must know that some billion people go to bed hungry every night, with no relief in sight? Mortality statistics are also skewed heavily in favor of wealthy countries. So yes, those of us in the industrialized nations are—again, depending on our class standing—living longer and eating better than in the past, but only at the cost of tremendous draining of resources from other parts of the world, and at increasing costs in terms of our own health. Just as HIV/AIDS is the scourge of the less developed world, cancer, asthma, heart disease and diabetes are the bane of the developed world, and all are related to the toxic chemicals we ingest, along with too much highly processed, sugary, fatty foods.

- For someone who is calling the organic movement “romantic,” Cohen seems to have an almost childlike confidence in authority figures. He says he trusts “the monitoring agencies that ensure pesticides are used at safe levels — a trust the Stanford study found to be justified.” And I suppose he also still believes in Santa Claus? We cannot trust that the “safe levels” established by the EPA or FDA are in fact safe, given the fact that we operate in an environment where thousands of chemicals enter the market without sufficient testing, presumed innocent unless proven guilty—but to win the case against them, first people must get sick and die.

- Cohen’s zinger, “I’d rather be against nature and have more people better fed,” displays his own breathtaking blind spot as regards the human relation to the natural world. Human beings cannot be “against nature” without being “against ourselves.” We are a part of the natural world just like every other life form on this planet. Our fantasy that we can use our technological prowess to completely divorce ourselves from our material, physical reality is just that—a fantasy. We eat by the grace of nature, not by the grace of Monsanto.

For the entire history of homo sapiens, we have always eaten organic. It’s only been in the last 50-odd years, post World War II, that wartime chemicals and technologies have found new uses in agriculture.

The result has been the rapid and wholesale devastation of vast swaths of our planet—biodiversity giving way to monoculture, killer weeds and pesticide-resistant superbugs going wild, the weakening and sickening of every strand of the ecological web of our planet.

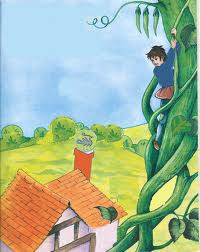

The relevant fable to invoke might be the tale of Jack and the Beanstalk. We might be able to grow a fantastically huge beanstalk if we fed it with enough chemical fertilizers, and we might even be able to climb it and bring back a goose that lays golden eggs.

The relevant fable to invoke might be the tale of Jack and the Beanstalk. We might be able to grow a fantastically huge beanstalk if we fed it with enough chemical fertilizers, and we might even be able to climb it and bring back a goose that lays golden eggs.

But in the end, that beanstalk will prove to be more dangerous to us than it’s worth—we’ll have to chop it down, and go back to the slow but solid organic way of life that has sustained us unfailingly for thousands of years.