There is a passage in my memoir where I describe the sense of gleeful abundance that the Christmas season brought to my childhood. It was a magical spell created through the transformation of bringing a fragrant pine tree into the living room and decorating it with lights and ornaments; the joyful anticipation of presents; the sweet and savory scents and tastes of my mother’s special holiday meals and treats.

Outside our home, the whole world was transformed by millions of lights, Christmas trees and decorations, the landscape glittering with lights on the ground and bright stars overhead. The cumulative effect of all of this was that for the holiday season, we seemed to have stepped over some kind of threshold into a magical fairyland, complete with talking reindeer that could fly and jolly elves that delivered presents down the chimney.

Nowadays, as an adult with children of my own, the external trappings remain the same, but it’s harder to recapture that sense of magic. The setting up and taking down of the Christmas tree, lights and decorations are chores, though there is pleasure in the outcome. The presents must be chosen, obtained and wrapped. The cooking must be planned and executed. My mother, on whom most of the burden of all of this activity fell in my childhood, made it look easy and fun, and I followed in her footsteps while my children were small, which is why they too have developed a magical attraction to celebrating this holiday in an all-out way.

As I grow older, it is harder to banish the persistent doubt…the feeling that rather than celebrating the birth of a sacred child representing love, mercy and compassion, or even the simple return to light of the Solstice, we in modern America have been charmed into celebrating the great God of Consumption, who we worship through the rituals of shopping, cooking and eating to excess.

Oh, I know I will be branded a Scrooge or a Grinch for this thought. My children will cringe, embarrassed that their mother would be willing to publicly deviate from the established tradition, the script. And I can’t deny that I still enjoy the chance to escape into fairyland for a day or two, through a door that only opens at Christmastime.

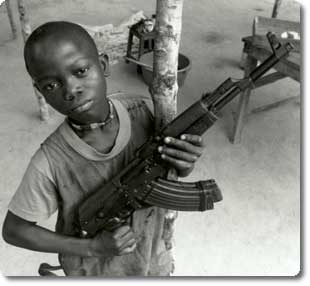

But while we fortunate few are enjoying ourselves with feasting and gifts, the unpleasant reality continues for the majority on our planet. Humans continue to kill and persecute other humans. We continue to kill and exterminate other species. The roasting of the planet through carbon combustion continues unabated, with weird, dangerous weather becoming more commonplace every day.

Oh Grinch, stop it, they will cry. Where is your sense of fun and joy? Why is your heart ten sizes too small?

No, I will reply sadly. The problem is that my heart is ten sizes too large, and I cannot relax in fairyland knowing that there is so much misery going on just outside our charmed circle.

This holiday season I have not been able to evade the thought that maybe what I need is a little dose of Zoloft to keep my mood suitably elevated and banish the darkness to the margins of my consciousness. Oh brave new world, in which we cannot function without a dose of manufactured, pharmaceutical good cheer!

If I were to change this holiday so that I could truly be happy celebrating, what would I change? I would still want to eat and drink and exchange presents with my family. But I would want to increase the dose of spiritual energy running throughout all the rituals. Instead of buying presents, we would take the time to make them for each other, putting love into every stroke of creation. Or at least choose and purchase gifts that are made by hand, with love.

We would take the time to appreciate the slow return to light that happens after the Winter Solstice, the sun going down just a few minutes later each day. We would go outside under the stars and moon and send our own intense lovelights into the universe, seeking consciously to increase the network of loving connection across the planet. We would affirm to each other our commitment for the coming year to each do what we can, in our own sphere, to make this world a better place for all.

We would take it all slow, as is appropriate for this dark, cold time of year. We would sleep in and go to bed early, allowing plenty of time for dreams. We would linger long at the table and by the fireside, enjoying each other’s conversation and company.

So much of contemporary life is about maintaining our robotic rhythms without any heed for the change of seasons. In the summer we air condition so we can keep working without the indolence of heat and humidity. In the winter we have the bright glare of electric lighting to keep the darkness of the season at bay, so we can keep working and playing without interruption.

These artificial rhythms are not good for our spirits—or for our mental health. As we are drawn into marching to the beat of the machine world, the bright living aura that tunes us into the pulse of life on our planet is diminished, dimmed.

It is no accident that our time has seen a resurgence of fascination with zombies, the walking dead. We play out in our imaginations what we fear in reality. Sometimes fantasy anticipates or spells out a frightening reality we do not want to acknowledge.

We must blow gently on the embers of our humanity, still alive and glowing despite all those artificial lights. In these Solstice days of dramatic darkness and light, let us cast the spell of the season by reaching out in love to each other and all life on the planet. That is where the true magic lies.

In my work—

In my work— We have a candidate for the American Presidency now who is not afraid to take up these values and call them by their old, 20th century name: socialism.

We have a candidate for the American Presidency now who is not afraid to take up these values and call them by their old, 20th century name: socialism.