When asked by young activists where they should direct their energies, Julia Butterfly Hill responds simply, “Everyone has to find their own tree.”

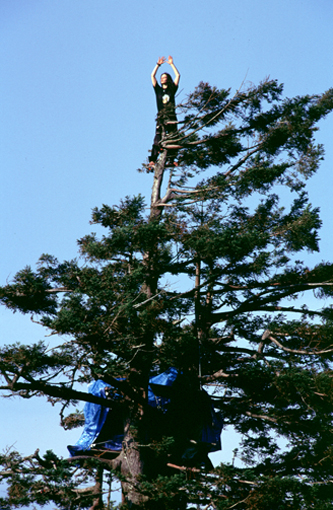

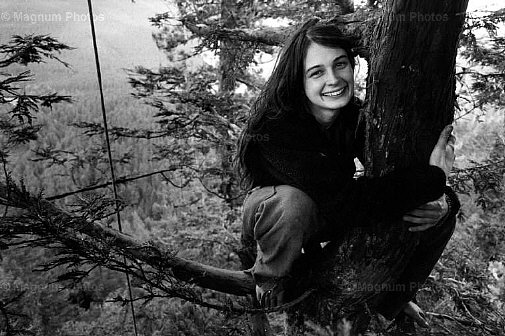

Julia, you may remember, is the woman who in 1997, at the age of 23, camped out at the top of a thousand-year-old, 180-foot-high California redwood named Luna, to save her and others in her grove from death by logging. She stayed up there for two solid years, through winter snowstorms, attacks by helicopter and constant harassment from the company goons holding siege below.

Julia, you may remember, is the woman who in 1997, at the age of 23, camped out at the top of a thousand-year-old, 180-foot-high California redwood named Luna, to save her and others in her grove from death by logging. She stayed up there for two solid years, through winter snowstorms, attacks by helicopter and constant harassment from the company goons holding siege below.

She eventually returned to the ground when her mission was accomplished—she had persuaded the logging company to leave Luna and her stand of old-growth trees alone. It was an important battle on the way to having the 7,500-acre Headwaters Forest protected as an ecological preserve.

This week we witnessed another brave young woman warrior, Sophia Wilansky, standing up to the attackers at Standing Rock and getting her lower arm blown off by a grenade.

Compared to the scale of the harm inflicted by the U.S. military in places like Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, a young woman losing her arm seems relatively minor. The water protectors are being hit with water cannons and mace, not cluster bombs.

But by the standards of what is considered acceptable behavior for American law enforcement against unarmed citizens, what’s been going on at Standing Rock is totally outrageous.

Without in any way undercutting the incredible sacrifice that young Sophia Wilansky has made, I want us to notice that when one white woman gets hurt, suddenly the outrage of the onlookers jumps up several notches.

Native people have been getting injured with rubber bullets fired at close range; elders are being beaten up; water protectors have been thrown into dog kennel cages and kept there in inhumane conditions; they’ve been attacked by drenching water cannons in 20-degree temperatures, with no way to get warm.

And there has been outrage and solidarity from onlookers: marches and rallies in many cities and towns, an outpouring of donations of food, warm clothing, camping supplies and money for legal fees and other expenses. The indie media and social media have been out in force, covering the scene.

But still, here we are on Thanksgiving, 2016, and Native Americans are being forced to fight, David vs. Goliath style, to defend their land and water from the rapacious appetites of the colonizers.

On this Thanksgiving Day, please take a moment to say a prayer for the water protectors of Standing Rock, who are standing up for the right of every American to clean water.

And please take a moment to think about Julia Butterfly Hill’s advice.

What is your tree? What is the cause that is calling to you with such passion that your heart leaps in response? Where will you stubbornly take up a stand, vowing not to give ground until the battle is won?

Be it noted that the Dakota pipeline was originally routed right next to predominantly white town of Bismarck ND. When the people there protested, the route was promptly changed. It didn’t require thousands of men, women and children, camping out for months; there were no water cannons, tear gas or rubber bullets used.

Be it noted that the Dakota pipeline was originally routed right next to predominantly white town of Bismarck ND. When the people there protested, the route was promptly changed. It didn’t require thousands of men, women and children, camping out for months; there were no water cannons, tear gas or rubber bullets used.

While outwardly conforming to the dominant beauty standards for women—dyed and coiffed hair, generous make-up, body-flattering clothing, heels—you also have to be commanding and aggressive, a no-nonsense sort of leader that everyone will automatically respect.

While outwardly conforming to the dominant beauty standards for women—dyed and coiffed hair, generous make-up, body-flattering clothing, heels—you also have to be commanding and aggressive, a no-nonsense sort of leader that everyone will automatically respect. Trump is like a stand-in for every boorish man who ever held power in America, whether a boss or a husband, a rich client or a random stalker on the street. Men like Trump elevate their own fragile egos by putting down others, with women being a convenient, always-in-view set of targets.

Trump is like a stand-in for every boorish man who ever held power in America, whether a boss or a husband, a rich client or a random stalker on the street. Men like Trump elevate their own fragile egos by putting down others, with women being a convenient, always-in-view set of targets. Perhaps that was part of what I admired so much about Bernie Sanders—his easiness with being nurturing and warm, even cuddly, on the campaign trail. No doubt this gentleness comes easier for men as they age and no longer have to prove themselves through aggression.

Perhaps that was part of what I admired so much about Bernie Sanders—his easiness with being nurturing and warm, even cuddly, on the campaign trail. No doubt this gentleness comes easier for men as they age and no longer have to prove themselves through aggression. Whenever I turn away from the glare of the brightly lit television screens and stage sets of our political moment, back to the green and gold of the forest, I am reminded of what really matters. The

Whenever I turn away from the glare of the brightly lit television screens and stage sets of our political moment, back to the green and gold of the forest, I am reminded of what really matters. The  This question became increasingly central for me as I worked on my memoir,

This question became increasingly central for me as I worked on my memoir,

This is such an exciting time to be alive. There is so much potential for human beings to take an evolutionary leap away from the tribal competitiveness and heedless destructive ignorance of the past, stepping at last into our full potential as the sacred guardians of the complex ecological web of this planet, which we are finally beginning to understand. The leap won’t happen without our giving ourselves permission to honor our deep connections with each other and with Gaia; without our giving ourselves permission to love.

This is such an exciting time to be alive. There is so much potential for human beings to take an evolutionary leap away from the tribal competitiveness and heedless destructive ignorance of the past, stepping at last into our full potential as the sacred guardians of the complex ecological web of this planet, which we are finally beginning to understand. The leap won’t happen without our giving ourselves permission to honor our deep connections with each other and with Gaia; without our giving ourselves permission to love. NOTE: My title is a take-off on Audre Lorde’s famous essay “Poetry Is Not a Luxury.” Poetry, as she lived and practiced it, was love. A few lines from the essay that I go back to again and again: Poetry “forms the quality of light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought….Poetry is not only dream and vision; it is the skeleton architecture of our lives. It lays the foundations for a future of change, a bridge across our fears of what has never been before.”

NOTE: My title is a take-off on Audre Lorde’s famous essay “Poetry Is Not a Luxury.” Poetry, as she lived and practiced it, was love. A few lines from the essay that I go back to again and again: Poetry “forms the quality of light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought….Poetry is not only dream and vision; it is the skeleton architecture of our lives. It lays the foundations for a future of change, a bridge across our fears of what has never been before.”

Tis the season of Commencement speeches, and I

Tis the season of Commencement speeches, and I